Diario del Sorpasso. 8 de junio.

La lectura del sorpasso desde una visión global lo enmarca claramente en el agotamiento del discurso de los partidos socialistas europeos. No es algo que le pase exclusivamente al PSOE, le ocurre a todos los viejos partidos socialdemócratas. En cada sociedad existen condicionantes particulares que trasladan de diferente forma esta tendencia a los sistemas de partidos nacionales. El caso extremo es el colapso del PASOK en Grecia, cosa que no ha ocurrido de forma tan dramática en el estado español. Pero el denominador común en toda Europa, es que la irrupción de nuevos actores políticos lleva a los viejos socialistas a la irrelevancia o a una posición secundaria desconocida para ellos en los últimos 50 años. El PSOE ha seguido el mismo camino de recluirse en los cada vez más estrechos márgenes del neoliberalismo salvaje, y no ha opuesto mucha resistencia. Esa mimetización acaba pasándoles factura cuando en un contexto de crisis, se visibilizan las consecuencias de sus políticas. Su falta de legitimidad para articular un discurso alternativo creíble es muy profunda y no se salva con candidatos algo más jóvenes que se arremangan la camisa.

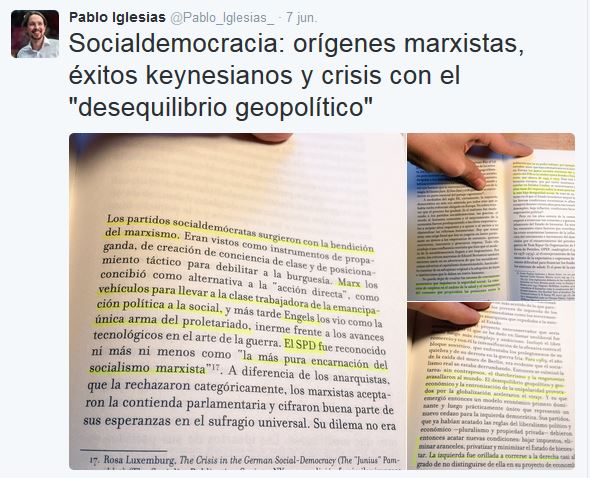

Errejón comenta en el documental «Política. Manual de instrucciones» de Leon de Aranoa, que en la batalla política, las palabras son colinas que hay que defender y conquistar. Pablo Iglesias trato ayer de reconquistar la colina semántica «socialdemocracia». Es un gesto electoral, pero detrás de ese gesto hay mucho más.

Esta es la lectura que hace The Guardian

The Podemos surge is a wake-up call for the European left

Paul Mason

Three days after Britain votes on Brexit, Spain faces a general election, the result of which could be even more decisive for the future of the EU. The Spanish radical left party Unidos Podemos has surged into second place in the latest opinion polls, and is currently on 25.6%. The position is remarkable for the fact that, unlike in Greece, the mainstream Spanish socialist party, PSOE, has not collapsed, but rather shrivelled back to 20% as the radical left gathered momentum. Together, Podemos and the socialists could, if the polls are right, form a coalition government in which the left’s ponytailed leader, Pablo Iglesias, becomes prime minister. For a party that emerged out of the street protest movement of 2011, these are spectacular gains. And, for Europe, uncharted waters.

How we got here is, in part, a story about a sickness built into the structure of the EU. In Britain, it is common for the left to argue “austerity is a political choice”. But, in the eurozone, it is mandated by the Lisbon Treaty, and by the stability and growth pact rules that penalise countries if they run deficits and debts in excess of EU targets. When, in 2010, Spain came to the end of a property boom that had seen students quit university to become bricklayers, its local savings banks collapsed. The resultant bonfire of illusions revealed the political establishment on both sides – socialist and conservative – as deeply culpable in corruption scandals.

With 20% unemployment, falling real incomes and a youth generation forced into emigration or precarious work, the frustration exploded – at first on to the streets. The initiators of May 2011’s protests developed an essentially “horizontalist” project – to replace a corrupt parliamentary democracy with local assemblies and voting based on consensus. Theirs was a critique of the entire system, not just its incumbents. And, at the outset, it was a movement that eschewed traditional left versus right labels.

Rubber bullets, a legal crackdown on dissent and yet more austerity propelled the 2011 movement into politics. Their first attempt to create a party – Partido X in 2012 – gained just 0.64% of votes cast. The second, Podemos, launched in 2014, caught the imagination not just of the unorganised youth, but also of a generation of intellectuals, creatives and community organisers who had excluded themselves from mainstream politics. Podemos scored just under 8% in the EU elections of 2014, but took control of three major cities last year – Barcelona, Valencia and Madrid – by forming broad community coalitions with local activists on housing, human rights and corruption. Now, by fusing with Spain’s traditional communist party, Podemos looks to have gained the velocity it needs to come second. That will force the Spanish socialists to consider a coalition with a newly dynamic and more powerful force to its left.

Social democracy’s electoral decline – from Scotland to Poland – is rooted in its attachment to free-market economics, which it needs to deliver rising wealth and wellbeing for the broad mass of people. The years since 2008 have shown that it does not and it cannot. From Matteo Renzi in Italy to Kezia Dugdale in Scotland, a generation of technocratic centrists across Europe have found that personal charm and modernity cannot counteract the toxicity of a form of economics that brings only inequality and stagnation. The paralysis of the centre-left presents their radical challengers with both a historic opportunity and a challenge.

Advertisement

The opportunity – as in Greece – is to become something close to a “natural party of government” for the networked generation that has lost out during the post-2008 crisis. The challenge is how to maintain the radicalism while enmeshed in the tangled web of power. In the cities the left controls, Podemos MP Pablo Bustinduy told me last week, “the biggest frustration is the amount of time it takes for a decision to leave the mayor’s office and actually take effect in society”. Welcome to the real world, a weary generation of centrist technocrats might sigh.

Podemos, like Syriza, has already sidelined its commitment to leaving Nato. Its real problem is going to be, again, the rules of Europe – which mandate punitive action by Brussels against a government that wants to cancel austerity and stimulate growth. “It would be unwise to reveal our tactics in advance,” Bustinduy told me, but he was clear the baseline for any left-left coalition in Spain would have to be in spectacular defiance of Europe’s deficit limits. Asked why this would end any better than Greece’s clash with the eurozone, Bustinduy highlighted the words “systemic risk”. Spain is too big to force into default, is the assumption. Whether such a radical intent could survive the need to build coalition with the centre-left is one question. The more fundamental question is: can the modernisers of the Spanish centre left find the courage even to try it?

What faces PSOE leader Pedro Sánchez is the dilemma that faces UK politicians such as Yvette Cooper when responding to the Corbyn phenomenon. Centre-left socialism is still in the anger-denial stage of grief; it has advanced no theory of its own ineffectiveness and produced no substantial account of how it alienated large parts of its voting base – both among the progressive salariat and the traditional working class. The temptation for the mainstream Spanish socialists will be to form a coalition with the right in a last-ditch attempt to deny reality. This would be bad for the left in Europe full stop. All across Europe, social democrats need to say to their Spanish counterparts: form an anti-austerity coalition and redefine centrist socialism around something better than the dole queue and the riot policeman’s stick.